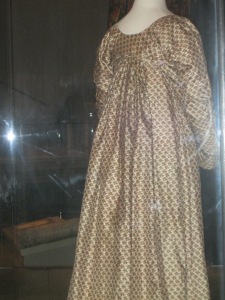

I love the print on this dress! Again, I never would have guessed it was authentic to the period. Click on the photos to zoom in. Here’s the photos:

I’ve got so much to post, I don’t know where to start. I’m working on a gown for Karen Millyard, plus I have all of my old Regency ballgown photos. But here are some shots of a 1810s gown and cape at the ROM.

I have to admit, the pattern of this dress is not my style. But the sleeves and silhouette are great!

It looks like the bodice is separate from the skirt. There’s a possibility that the cape is attached to the bodice, so that it makes a coat. I think I’ll need to visit the gown again and get a closer look. But, my guess is that this outfit consists of a dress and a caped jacket, the front of the jacket closing in buttons, with the cape part closing with a hook at the neck. Must revisit to clarify.

Click on the photos to zoom in.

Posted in Antique Gowns, Regency | 4 Comments »

I have a ROM membership, so I visit often. I ventured to the fourth floor for their Riotous Color exhibit, and took some photos of their 19th century gowns for the world to see and study. Since this is all so image rich, I will post each gown individually.

The ROM describes this patterned silk dress as being semi-formal. I would guess they came to that conclusion for the following reasons:

1. It’s made out of silk, which is a formal fabric.

2. It’s not decorated heavily, which would suggest that it is not a super formal dress.

3. It is long-sleeved. Many of the ballgowns of the period were short sleeved.

4. It has a train, which would suggest that it is formal. However, in the first half of the decade, almost all dresses had trains, regardless of their formality and purpose. There were many complaints made during the day about how women of all classes would be gathering up their long, dirties trains. But throwing the train over one’s elbow allowed a woman an opportunity to show off her legs.

5. I am no expert on printed fabrics, but I am guessing that a printed silk would be expensive. Dyes on silk do like to run, and a multi-colored wood-blocked print would probably be pretty difficult. Yet, the long sleeves and lack of decoration suggest the gown is not meant for very formal wear.

I would guess that a printed-silk, trained gown would be worn at home by a relatively affluent woman.

Here’s the photos:

GOWN 1800-1805

The gown is made of printed silk with a straight front. Long sleeves that cover the wrists, straight line across the neckline. The female figure is columnar, yet active. The architecture of the gown does not create the body, unlike the previous era. This is a reflection of the chaotic social mobility of the era.

Pleated, high waisted back with train. Straight front. Very typical of early Empire. The train becomes an extension of the neck, the whole thing culminating in a head crowned in soft curls.

Posted in Antique Gowns, Jane Austen, Regency | Tagged 1805 gown, Empire Fashion, Jane Austen Costuming | Leave a Comment »

PHOTOS OF THE GOWN DETAILS

Side shot of the back of the gown. Due to time limitations, the closure was quickly done. I used hooks and eyes, and an attached sash. In the future, I will probably take these out and handwork some lacing holes.

Detail of the sleeve embroidery. This is a great shot of my stitching too, which was an exercise in precision and very time consuming! The results were gorgeous.

I cut very carefully around the embroidered panels, cutting as close to the embroidery as possible without cutting the stitching. Below the panels I attached a gathered sash made from the gown fabric.

This shot shows the spacing of the panels. The sash was gathered and sewn at points. It was basted between the gathers. This is a very period treatment for the hem.

Close up of a warm-colored embroidery panel and the gathered hem sash. There were six panels in total. I alternated between the color schemes. They reminded me so much of the tile patterns of Istanbul. The embroidery is beautiful, and is hand done (though not by me!).

Cutting the embroidered panels was a test of the nerves. There’s not a single straight line on them, and a millimeter in the wrong direction would result in catastrophe. Stitching them on by hand was very precise work. The stitching needed to be close not only to attach the panels but also to prevent future fraying. Some of the photos show the hand stitching, and I am remarkably proud of that work.

The hem sash was easy enough, and it looks pretty and highly authentic. It was a quick way both to cover the stitches used to hold the hem (so I did not bother to make them inconspicuous. One must pick one’s battles!) and keep the beautiful embroidery off the ground. I decided to treat the sleeves with the gathers so as to echo the pointed arch of the embroidery. In keeping with the gathering theme, I attached the gathered sash. Should the hem become soiled in the future (should I wear the gown again!), I can always add more trim. It means a lot to me to have it function as though it were a “real” dress even if I don’t wear it more than once. I like knowing that the gown will function as a piece of clothing, and not just as a costume.

I’ll post some photos of it being worn in a bit.

Posted in Uncategorized | 2 Comments »

I was fortunate enough to get my gown finished just in time for the Jane Austen Ball in Toronto at St. Barnabas church on Danforth Avenue. It was held last night. This was the first event of this nature I have attended since arriving to Toronto nearly a year ago.

Jane Austen Ball 2012. I have few photos. Once the music started, no one sat out of the dancing including myself.

Let me start by commenting that many who are interested in historical costuming and historical dance find themselves too few in numbers (and/or too short on commitment) to bring a large scale historical reenactment to fruition. Even beyond that, often the events can be bogged down by superfluous structure and hierarchy which only deters joviality and new interest. This is the plight of the historical costumer: where can one make their historical garments “live” by wearing them, socializing in them, and putting them in the context in which they were made to be worn without the cooperation of earnest and like-minded individuals?

Setting up a historical reenactment requires a multitude of skills and an interested community. One is dealing operationally with 2012, trying to evoke 1812, and stir up enthusiasm and sentiment enough amongst the participants to make the whole thing fly. Unlike a theatrical event, at reenactments your performers are also your audience, your costumers, and your financiers. One can’t direct them and expect them to follow blindly. For success, there must be interest and good will. In this most crucial of areas, the 2012 Jane Austen Ball was a complete success.

Granted, there was room for improvement. The interior of the event space was hardly Adamesque. The punch, though based on a researched historical recipe, was not cupped in fine china. No one brought out the sterling to dish out the fresh fruit and tasty little cookies. There were no silk-clad Empire chairs on which to rest while officers gathered round to claim your hand for the next dance. And where were the torch-holding footmen? But one would be a very sad person indeed to complain about the wonderful music, the beautiful dancing, or the assembled polite society. In these areas, improvement would be difficult.

In summary, the Jane Austen Ball displayed the magnificent attributes that attracted me to historical costuming and reenactment in the first place: the pursuit of an aesthetic motivated by joy, formed by work and study, and directed by ideals, the result of which is a sensory experience whose remnants linger in the mind similarly to how the remnants of an era linger in the museum or the book. But unlike the static nature of those latter fossils, historical costuming and reenactment have the power of being in the present on the day they occur and being remembered by those who were never there.

Historical costuming and reenactment is not about denying the present or the future. It’s about bringing things to existence, where historical study provides a few pointers. One learns a great deal through study even if only by virtue of the study being an effort made. But it is a joyous moment when the study and effort can be brought some fruition. A gown never worn or project never started is a sad thing indeed. And last night was the successful completion of a happy project for many.

Can’t wait to make something new for the next one!

Posted in Uncategorized | Leave a Comment »

Here are the sleeves. I lined them in muslin and attached some embroidery at the shoulder top. They turned out quite well.

I’ll be posting photos of the whole gown shortly as well as a piece on the Jane Austen Ball here in Toronto.

Posted in Uncategorized | 1 Comment »

I’ve gotten the hem of the skirt finished. To decorate the bottom I have some gorgeous silk panels embroidered in silk. I carefully cut around the outside edge of the embroidery. To attach them I will precisely hand sew the outside. I did the same with the finished bodice, and it looks stunning.

Because I am attaching these delicate silk embroidered panels to the hem, I will add some hand made silk trim to the bottom to take the wear. I haven’t decided yet whether to make the trim in ivory silk or make it of a coordinating colored silk that will match the sash and the turban. I think I will end up doing the latter, as it will probably save me a lot of heartache when the hem is inevitably soiled.

I have a confession: I am sick of ivory silk. This is the first time I have tired of a material I was working with. It looks beautiful and feels beautiful, and I recognize it will make a fantastic dress. But It has not the impact and drama of a deep rich color or outstanding pattern. Also, I every time I try the dress on I realize that it is not flattering either. But, I am confident that the results will be gorgeous and very Regency.

Posted in Uncategorized | Tagged Regency Costume | Leave a Comment »

Not much to look at yet, but a lot of work has been done. There are four pleats under the bust. The front panel of the skirt has four right angles and is not pleated. The two side panels are cut like wedges, keeping the front straight and column-like.

I’ve been pretty neglectful about updating my Regency ballgown costumes. Here’s a quick update:

Most of the necessary work for the ballgown is complete. What remains are the sleeves, the hem decoration, back bodice closure, and a good pressing. Normally, I finish the bodice completely before sewing on the skirt. But the skirt will need significant hand sewing and I have more time available for hand sewing than for machine sewing. A heavily hand sewn hem can’t be decorated until a hem line exists. So, I sewed on the skirt to get a proper hemline measurement.

Back seaming. The back waist is higher than the front waist which is in keeping with the fashion of the time.

Unfortunately, ivory silk does not photograph well at all. But the fabric, fit, and construction are gorgeous. The bodice is interlined in cotton. I finished off the edges by turning them under and whipstiching, being careful to catch the interliner only with the stitches so no stitching shows. I debated doing a liner in silk, but I decided against the additional bulk. I am sewing a Regency gown after all, not an Elizabethan. Light and diaphanous was the order of the day. The cotton gave it additional body and reinforcement. The ivory silk is a little sheer (I can’t wear black underwear!), which is totally in keeping with the fashion of the era. I’ll be wearing a petticoat underneath, but I think the lining on the bodice was a good idea. In case I change my mind and decide to add a silk liner as well, I have the silk liner cut and pinned.

Unfortunately, white has never photographed well. Here is a sideshot of the bodice with the skirt attached. The back panels of the skirt are pleated into the back of the bodice, which maintains a column-like front but allows for graceful movement. Regency women looked long and columnar, but graceful and unconstrained.

I was planning on making a jacket to go over the gown, but the bodice looks so lovely that I’m not sure I can bring myself to do it. Also, I drafted the pattern myself, and it fits like a glove. A jacket could cover up shoddy work, but I don’t have any shoddy work to cover up.

The gentleman’s costume has suffered from a reduced priority level. I will be very impressed if I can get it done by Saturday.

Posted in Uncategorized | Leave a Comment »

I’ve made considerable progress on my own Jane Austen-weekend ensemble. It will be lovely!

I drafted the pattern for the gown myself based on period pictures, and have the skirt already sewn and cut. The bodice interliner is cut and fitted.

The dress will be decorated at the hemline and neckline with some of the finest pieces of hand-embroidery I have ever owned. It is persian design done with fine silk stitching. The gown itself is made of warm ivory dupioni silk. Over the gown will be a colored silk vest that will be cut to show the embroidery on the bodice. I will wear the gown with a turban and an ostrich feather.

I’ll post pictures shortly and perhaps a bit about Regency-era Orientalism shortly. The gown looks amazing!

Posted in Uncategorized | Leave a Comment »

Cavalier King Charles Spaniels have so much in common with historical costuming: the breed is a reproduction of an extinct breed based solely on portraits and accounts written by people long dead.

Mary I and Philip of Spain and their spaniel. They were popular in the 16th century. In the 17th, they were the epitome of aristocratic companionship. King Charles never went anywhere without his spaniels.

Both fashion and dogs have geneaologies, as they are born from lineages and mutations. No dog breed, or fashion can exist without a history and origin of it’s components. Dog breeding, like fashion and clothes, has it’s roots in the quest for human delight, pleasure, and comfort. Genetic analysis of dog breeds has determined that humanity originally bred dogs with the purpose of companionship in mind, which is not really what one would have guessed. One can imagine that the life span of working dogs in the early stages of mankind was pretty short, so numbers – not quality – would have been most important. If they did breed their working dogs, geneticists have been unable to find any modern evidence of the fact. But there is evidence that when mankind started breeding dogs it was temperament, not strength or work-capacity. And a Cavalier King Charles is a perfect example of a dog meant solely for companionship.

Non contemporaneous depiction of King Charles`French Queen. She is depicted as maternal: floating in an idyllic existence with her children and a beloved spaniel.

Yet, my purpose here is not to discuss the merits of this docile, non-aggressive, loving breed, or it’s eager quest to find a warm friendly lap on which to relax. What does interest me about the breed, and what it shares with historical costuming, are the origins of it’s modern form.

The original King Charles Spaniel was an early modern creation. Brought to England from the continent, they were made intensely popular by King Charles I before he lost his head in the Civil War. In the restoration era, they were still inhabiting the neoclassical halls of the English aristocracy but their population substantially decreased over the next century. In a sense, they did disappear eventually, as by the Victorian era the King Charles Spaniel looked very different from what we have in portraits. In 1845, William Youatt commented “The King Charles’s breed of the present day is materially altered for the worse. The muzzle is almost as short, and the forehead as ugly and prominent as the veriest bull-dog. The eye is increased to double its former size, and has an expression of stupidity with which the character of the dog too accurately corresponds.”

A small pup on the lap of a lady. Numerous portraits with King Charles Spaniels exist, and served as part of the basis for the 20th Century reconstruction of the breed.

In the early 20th century, an eccentric millionaire offered a sizable sum to any dog breeder who could reproduce the King Charles Spaniel from the 17th Century. Dog breeder associations had a good laugh at this amateur, rather pointless (to their minds) effort to recreate a dead aesthetic. Sadly, the gentleman who started the project died before it reached its completion, a completion it almost didn’t reach. During World War II, the quest for the 17th century spaniel of the decapitated king was nearly lost yet again. The leading kennel which was making the effort found their 60-dog kennel cut back to 5 or 6 dogs as a result of war rationing, general lack of resources, and waning support for an whimsical project to breed a toy dog belonging to an absolutist king. It is from this small surviving population that all modern Cavalier King Charles Spaniels descend.

Last of the long-nosed King Charles Spaniels (early 19th Century) before crosses with the fashionable Victorian pug turned their noses up forever.

Historical Costuming and the Cavalier King Charles Spaniels have a great deal in common, therefore. They were both reproduced from beautiful period portraits, drawings, and written accounts of people long dead. They were both endeavors born from eccentricity and nostalgia. And both are very friendly, very non-threatening, beautiful to look at, and they keep you nice and warm.

Why am I writing about these dogs? Because I just got one. She is a beautiful, Blenheim blue blood and such a lover!

Posted in Uncategorized | Tagged Cavalier King Charles Spaniel, Costuming, Historical Costuming, Spaniels in portraiture | 1 Comment »

To get in the mood, I am reading Carolly Erikson’s history of Regency England. Erikson is a marvelous author if you already have some deeper background on the subject. One wouldn’t call her books academic as their subject matter is structured more to entertain and appeal to the senses, less to gain specific statistics, historic operational knowledge, or mastery of a specific subject matter. She’s something of a Mendelsohn – her work is lively and upbeat, good at creating a general mood, but not meant to be too heavily analyzed.

Her authorship betrays her Medieval History background, as I recognize the structure she uses in her writing as being relatively consistent with a number of more academic authors who write on more arcane subjects. There are plenty of Medieval authors who write sexy and visceral material, but when one looks for a book to read over the weekend, one seldom says “I would like to read material taken from interviews performed by Inquisitors on suspect Albigensian villages.” No. Typically when one reads historical nonfiction, one tries to evoke the mood of a era as they have associated it with some acquired cultural reference. Since one is reading “non-fiction” though, one may do so with the pretentious motivation of furthering the expansion of one’s mind.

I hope I am not being to critical when I suggest that one doesn’t need to read non-fiction to expand one’s mind. In the end, unless one is reading a very heavy academic book, one is still reading a story. And arguably a heavy academic book is simply a story written with lesser thought put towards aesthetically resonating with the mental processes of the reader. Numbers, for example, can tell stories if one is ready and able to devise theories for the stories between them. And, all historians are theorists. There is no way to “test” their theories as they conjecture about something long past and dead. But where would we be as a race if we did not theorize?

I digress! I will be posting some historical posts as inspired by Ericson’s book. I’m brewing something on the subject of “Regency Nightlife” as we speak.

Posted in Uncategorized | Leave a Comment »

Beau Brummell, regency fashion leader in his ivory pants. Millitary officers were, after all, fashionable attractions in ballrooms and in marriage.

I’ve cut out the pieces of my Jane Austen-era ivory wool pants. From what I understand, light colored pants were preferred for evening and formal wear. Ivory was also the standard color for millitary pants as well. White pants pair well with the image of the status conscious British redcoat with their formality and strict discipline. But in reality, their physical circumstances were dirty and trying enough to kill those with weak constitutions way before musket shots were fired. So, how do ivory pants fit into both the backdrops of the bloody battlefield and the boisterous ballroom?

Naturally, ivory and white pants are the hardest to maintain, and a clear pair of light colored pants would demonstrate that one had the lifestyle, habits, morals and capabilities to keep them clean. When one imagines all of the British army officers of the late 18th and early 19th century struggling to keep their clothes clean in almost all of corners of the earth, one is astonished that the British Empire was able to form at all. Discipline must be something like a muscle – the more one uses it whether in laundering, musket-loading, or cutting back gastronomically – the more it is able to give back. To a British army officer, keeping one’s pants clean may have been seen as a reflection of the care he was capable of putting into detail-oriented warfare.

I remember reading in one of my Jane Austen-context books that military officers were incredibly fashionable to have as guests and admirers. The army was more fashionable than the navy, and the higher rank the officer basically the more his appeal would be in a ballroom or dinner party. So, the appeal of the white/ivory pants in evening and high fashion wear was a reflection on how British manhood was defined. High maintenance but relatively durable pants were a commentary on the discipline, physical skill, and service to society a man could provide all while keeping his clothes nice and clean.

Anyhow, thinking about this won’t get my pants done. Off to work.

Posted in Uncategorized | Tagged Jane Austen Costuming, Regency Costume, Regency Costuming | Leave a Comment »